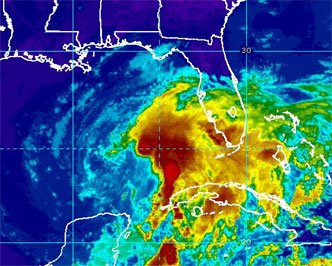

This article by Rick Lyman in today's New York Times provides some indication of the impact of Hurricane Katrina on the human landscape. It is based on a study conducted by the Census Bureau.____________________________________

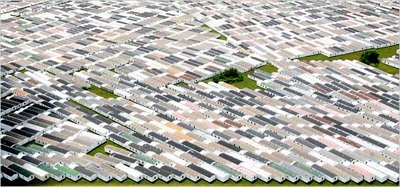

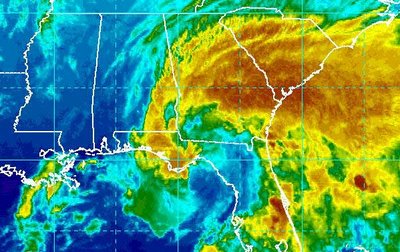

After the twin barrages of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita last year, the City of New Orleans emerged nearly 64 percent smaller, having lost an estimated 278,833 residents, according to the Census Bureau's first study of the area since the storms.

Those who remained in the city were significantly more likely to be white, slightly older and a bit more well-off, the bureau concluded in two reports that were its first effort to measure the social, financial and demographic impact of the

hurricanes on the Gulf Coast.

The bureau found that while New Orleans lost about two-thirds of its population, adjacent St. Bernard Parish dropped a full 95 percent, falling to just 3,361 residents by Jan. 1. The surveys do not include the influx in both areas that has occurred this year as more residents begin to rebuild.

While the New Orleans area lost population, the Houston metropolitan area emerged with more than 130,000 new residents, many of them hurricane evacuees. Whites made up a slightly smaller percentage of Houston's population — 62.8 percent of the city in January compared with 64.8 percent last July, a month before Hurricane Katrina hit.

In Harris County, which includes Houston, median household income fell to $43,044 from $44,517, while New Orleans area's actually rose, to $43,447 from $39,793.

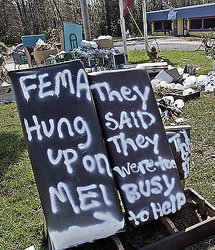

The physical impact of the hurricanes is well documented. Now, with these reports, bureau officials said they hoped to begin drawing into sharper focus the human landscape, showing in stark statistics how the storm's impact was felt most keenly by the poor, members of minorities and renters.

"One of the keys for me is that the data we are seeing really supports the anecdotal stories we've been hearing for months," said Lisa Blumerman, deputy chief of the bureau's American Community Survey. "We now have quantitative data that supports the stories from the storm."

One of the reports looked solely at population gains and losses, while the second studied demographic shifts before and after the storm.

The reports' findings had been expected, said William H. Frey, a demographer for the Brookings Institution. Still, he said, there were some small surprises.

It was not only New Orleans but also the entire metropolitan region that became whiter, less poor and more mobile, Mr. Frey said. At the same time, he said, assumptions that the evacuees who went to nearby Baton Rouge, where the population grew by nearly 15,000, were disproportionately poor and black were proven incorrect. A more middle-class group settled there, while the poorer and more vulnerable, who had less choice about where they landed, went to more distant cities.

Demographers in the affected states said yesterday that they were skeptical of some of the methodology in the studies, wary of the results and unsure how helpful the reports would be in measuring the human impact of the storms. Steve Murdock, the state demographer of

Texas, said the studies underestimated the number of hurricane evacuees in Houston by limiting their measurements to individual households and failing to count people living in hotels, shelters and other group environments.

"I can tell you that I learned nothing new about Texas," Mr. Murdock said. "These are very limited data. The truth is, nobody knows how good this data really is."

Caroline Leung, an economic researcher at Louisiana Tech University, said she had been trying to reconcile some conflicting data in the two reports and came away confused. The underlying trends may be valid, Ms. Leung said, "but I would not rely too much on those population numbers."

Census officials emphasized that the special reports used a somewhat different methodology than typical bureau studies, saying some of the numbers might be slightly less concrete than normal.

"But we felt the need to do this quickly, because the impact of the hurricanes on the Gulf Coast population is really without precedent," said Enrique Lamas, chief of the bureau's population division.

Of the 117 counties and parishes used in the studies — those identified by the Federal Emergency Management Agency as eligible for disaster assistance — only 40 lost population in the four months after the storm, and 99 percent of the losses came in the top 10 parishes and counties, comprising New Orleans and Lake Charles in

Louisiana and Gulfport and Biloxi in

Mississippi.

The black population of the New Orleans metropolitan area fell to 21 percent from 36 percent, the bureau found.

Photo shows Darwin Cooper, a worker at the General Motors Lordstown Assembly Plant in Lordstown, Ohio, standing next to the Cobalt assembly line on Wednesday June 21, 2006.

Photo shows Darwin Cooper, a worker at the General Motors Lordstown Assembly Plant in Lordstown, Ohio, standing next to the Cobalt assembly line on Wednesday June 21, 2006.